The Washington Post handed me a topic to write about today, but I’ve written a lot about problems, so after I write about “Layoffs” I’ll close with a Good News story from my desk research.

Before I get into those topics, though, I want to say something about the difference between AI and human intelligence. There are important philosophical issues to work out with the use of AI, so I want to cover a little philosophy here.

Humans are conscious, machines are not. I’ll write more about consciousness in the near future, but I want to use the example of ambivalence as the sort of thing machines can’t do. AI can write about Layoffs and Drug Discovery, but it can’t be ambivalent, and then work through ambivalence, as I am doing this morning.

One one hand, I thought that the Layoffs topic would be of interest to people who’ve been laid off, or fear getting laid off. Click-bait. Good for my numbers. On the other hand, I didn’t feel like writing about that. Why? Because I was laid off in December, and it still stings. And because I’ve written a lot about problems with AI, and would rather write a Good News story. Then I came back to the relevance of the story, and decided to do it.

Humans write what we are thinking and feeling.

We think about how it will be perceived by others, and how we want others to feel about what we write. In my first story about Chat GPT and a children’s story I used it to write, I made the distinction between the elements of the story that came from my intentions, which I believe made the story achieve my objectives, and the role that Chat GPT played in doing the writing.

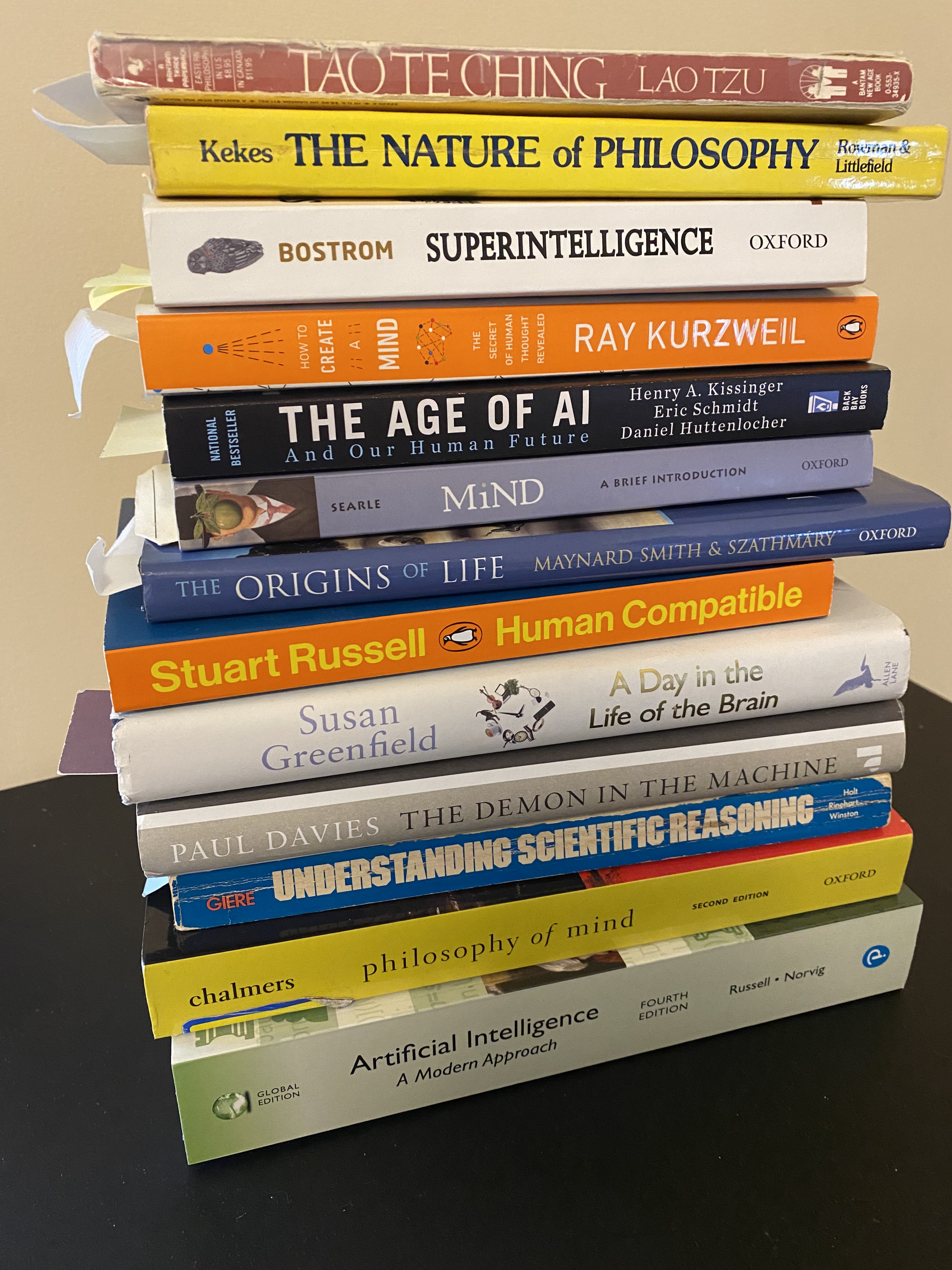

To quote Stuart Russell again:

Humans are intelligent to the extent that our actions an be expected to achieve our objectives.

Machines are intelligent to the extent that their actions can be expected to achieve their objectives.

“Human Compatible: Artificial Intelligence and the problem of control” 2019

Humans do what they decide to do. Machines do what they are instructed to do. Now I’ll move from philosophy to news.

Layoffs and AI

Pranshu Verma has a column called “Innovations” for the Post. Yesterday’s story was: “AI is starting to pick who gets laid off.“

He starts with news that Google had another round of layoffs, and speculation about whether they used AI to make layoff decisions. I suppose it was worth starting there, despite the fact that it was speculative, because of Google’s leading role in AI.

He went on to share some data that is not speculative, but is a bit ambiguous as to the role of AI:

A January survey of 300 human resources leaders at U.S. companies revealed that 98 percent of them say software and algorithms will help them make layoff decisions this year. And as companies lay off large swaths of people — with cuts creeping into the five digits — it’s hard for humans to execute alone.

The survey does not say that AI will make layoff decisions. It says HR leaders will use software and algorithms to help make decisions. Back to speculation – of the 98 percent, how many will rely heavily on the AI?

Verma interviewed Zack Bombatch, a labor and employment attorney and member of Disrupt HR, an organization which tracks advances in human resources. As an attorney, Bombatch is looking into the issues of bias or unfair discrimination that can arise from using algorithms that may be difficult to analyze for fairness.

So lawyers, HR and technologists need to come together on problems like these. An HR software company executive interviewed in the story expressed the key take-away from this article:

“It’s a learning moment for us,” he said. “We need to uncover the black boxes. We need to understand which algorithms are working and in which ways, and we need to figure out how the people and algorithms are working together.”

That’s the main idea I wanted to pull from the story, because it is a universal problem. It happens to come from a story about HR decision-making, but I was struck by the fact this quote in and of itself is a central problem that arises from the opacity of machine intelligence – in this case, the the HR leader can’t explain what happens under the hood, and lawyer can’t depose the AI. It’s the sort of thing we’re sorting out as we go.

And now some Good News.

This (short) story is adapted from “The Age of AI and our human future,” by Henry Kissinger, Eric Schmidt, and Daniel Huttenlocher, 2021 and 2022.

Researchers at MIT set out to use machine learning to see if they could uncover new antibiotics. The problem of drug-resistant infections has been growing, and the upward trend is alarming.

Researchers built a “training set” from two thousand molecules, and for each one, included its chemical properties, such as molecular weight, the types of chemical bonds, and its ability to inhibit bacterial growth. When it was done training, they instructed it to look at a dataset of 61,000 molecules and look for molecules that 1) it predicted would be effective as an antibiotic, 2) did not look like any existing antibiotics, and 3) the AI predicted would be non-toxic.

Good news! It found one! The researchers named the it “halicin” a nod to HAL from 2001: A Space Odyssey. When I was at Chemical Abstracts, I interviewed drug-discovery chemists. The drug-discovery process is immensely labor-intensive and time-consuming. The discovery of halicin was truly a break-through, and an indication of more good news to come from the power of AI.

Leave a comment