AI history is being made in February, 2023. Last week it was a sensational debut of the new Bing chat bot. This week (tomorrow), Google’s AI algorithm that decides what to display or not display on YouTube goes before the US Supreme Court in the case of Gonzalez v. Google.

An algorithm is a set of instructions written by a computer program. There’s a lot of math involved, but it’s basically a rule or set of rules that the program is instructed to follow. Google engineers write the algorithms driving content display, so Gonzalez’ attorneys are arguing that this is a form of “speech” on the part of Google.

So AI is challenging our understanding of what “speech” means, and who’s responsible when there’s a non-person, an AI agent, involved in the speech. I wrote recently about the disturbing speech coming from the Bing chat bot Sydney, and declared “we don’t want our children chatting with Sydney”. I wrote that statement, and it was an expression of my opinion. I’m responsible for it, in case Microsoft wants to take issue, it was me. I was not quoting someone else, and it was not generated by a bot.

The Gonzalez case is more complicated. Their daughter was killed in a terrorist attack, and they blame Google for leaving content on YouTube that was posted by ISIS and called for attacks on Americans. The videos stayed up for an extended period of time. They argue that Google was negligent in not removing them more quickly.

From the New York Times, this morning:

Their suit takes aim at a federal law, Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, which shields online platforms like Facebook, Instagram and Google’s YouTube from lawsuits over content posted by their users or their decisions to take content down. The case gives the Supreme Court’s justices the opportunity to narrow how that legal shield is applied or to gut it entirely, potentially opening up the companies to liability for what users post and to lawsuits over libel, discriminatory advertising and extremist propaganda.

NYT February 20, 2023

There are two parts of the protection: 1) content posted by their users and 2) their decisions to take content down. The algorithm is deciding what to take down. But the algorithm is written by Google.

This is an important question. What responsibility do the tech companies have for the actions that result from their algorithms? How far will this question go? I think most of us would like to see better monitoring of harmful content posted by users (Google), less “serving up” of controversial content (Facebook), and filters to prevent harmful speech from chat bots (Microsoft).

If Sydney got into the hands of children or mentally vulnerable adults in the form we saw last week, it could do harm. I’m sure Microsoft will take the risk of harm seriously, and act accordingly, but it’s not easy to do.

US federal law is under examination in the Gonzalez case this week. I’ve recently written about two other applications of AI that may challenge, or be part of the consideration of this law in the future. The Bing chat bot and the (Facebook) click-through algorithms.

AI pioneer Stuart Russell points to “faulty definitions of rewards” in the programming of these AIs, leading to unanticipated behaviors, and in the case of the click-through optimizers, I agree with Russell that they “seem to be making a fine mess of this world.”

Russell indicates part of the technical challenge for engineers, to make sure the programs are not defining “rewards” for the AI to pursue, that lead to unintended harm. The problem of making AI safe is a challenge. The Supreme Court will have something to say about one narrow aspect in this case.

So far, I’ve written about a potentially harmful bot, harmful click-through algorithms, and now insufficient content filtering algorithms. There’s a lot of work to do on Safety in AI. I’ll write more about it next week.

Comments welcome!

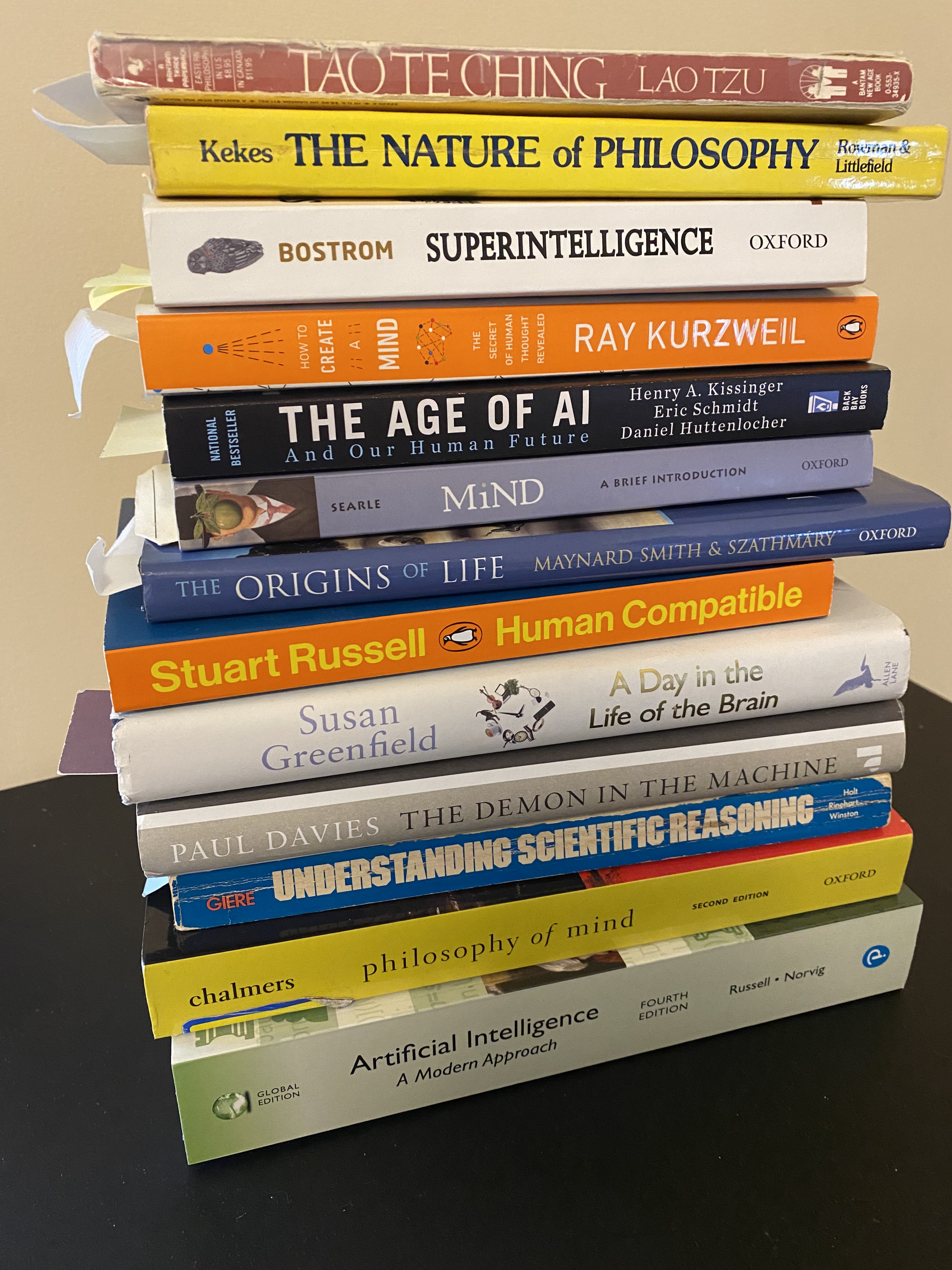

Reference: Russell, Stuart “Human Compatible: Artificial Intelligence and the Problem of Control.” 2019

Leave a comment